ABDOMINAL WALL HERNIAS: Types, Risk Factors, Diagnosis and Treatment

The role of the allied health community is critical in identifying hernias and determining if a patient requires referral for treatment or in some cases even deemed a medical emergency. With hundreds of patients coming through your doors for treatment each week and your teams undertaking hands on assessments, it’s very likely that you will may come across a lump or unusual swelling that may require further assessment. Furthermore, many patients are referred for physiotherapy or exercise physiology for groin pain or discomfort that is thought to have a musculoskeletal basis but may instead be due to hernia. Especially in overweight or obese patients it can be difficult to detect a small hernia. This applies especially to the more dangerous femoral hernias. Hernias may also cause pain or discomfort outside the groin, for example in the anterior thigh or hip region, leading to misdiagnosis and referral to allied health instead of sugery. Therefore it’s important you know what to look out for and the key risk factors.

What is a hernia?

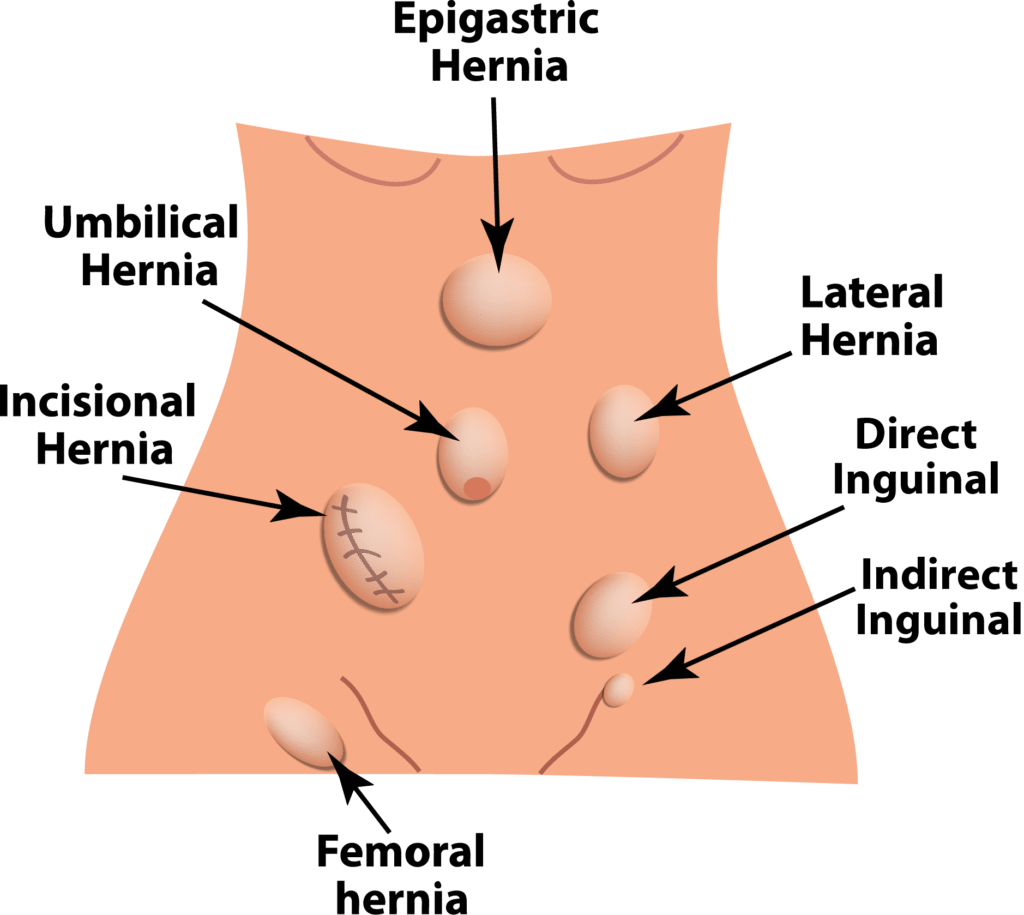

A hernia is described as a protrusion of an organ or tissue from its normal cavity pushing through a weakened section of the abdominal wall.

Protrusions outside the abdominal wall are reviewed here, but there are other hernias (such as hiatus hernia) that protrude between body cavities.

What are the different types of hernias?

There are several different types of hernias, these include;

- Inguinal (direct and indirect)

- Femoral

- Umbilical

- Incisional

- Epigastric, and

- Hiatal

What are the common risk factors for hernia development?

The risk factors for hernias often depend on the hernia type however come factors include;

Patient factors;

- Age

- Sex

- BMI, and

- Smoking

Obesity and smoking are risk factors for hernia recurrence and for wound infection. Therefore, smoking cessation and weight loss are strongly recommended prior to hernia repair.

External factors;

- Cumulative mechanical load or stress (physically demanding work, lifting weights, repetitive coughing)

- Defects in collagen and elastic fibre function, such as those with Marfan or Ehlers-Danlos syndromes, or polycystic disease

- Connective tissue variants – Some data suggests an aetiological role in the connective tissue many hernia types in patients without a phenotypic abnormality.

- Potential genetic variations including mutations have been identified that may link hernia development, connective tissue alterations and a complex multifactorial inheritance pattern for hernias is seen in some families.

Is it the hernia that is causing the pain?

It is important to clarify is that the hernia is really the cause of pain for the patient. Especially if it is a very small hernia detectable by imaging alone and is found in a young male, as this group has the highest rate of postoperative chronic pain following hernia surgery.

Specialised ultrasound examination, possibly MRI imaging, and referral to a sports physician are valuable in this group of patients, who often have a musculoskeletal cause for their pain. A hernia operation may worsen rather than relieve symptoms in these patients. The most valuable treatment for musculoskeletal groin pain is physiotherapy.

Operative techniques that seem to reduce postoperative pain include laparoscopic approach, possibly use of a larger pore soft mesh, and in my experience use of absorbable tacks and absorbable glue to hold the mesh in place, along with gentle tissue dissection (Figures 1 and 2).

INGUINAL HERNIAS (Groin Hernias)

There are two types of inguinal hernia:

- Indirect (lateral) hernias Indirect inguinal hernias occur lateral to the inferior epigastric vessels in association with the deep (internal) inguinal ring. Patency of the processus vaginalis plays a role in indirect hernia development in infants and children, and some adults.

- Direct (medial) Hernias Direct inguinal hernias herniate through a weakened transversalis fascia in Hesselbach’s triangle, medial to the inferior epigastric vessels.

The lifetime risk of developing a groin hernia has been estimated at 27% for men and 3% for women, and more than 20 million people undergo groin hernia surgery per year.

- Sex - Inguinal hernias are 9-12 times more common in men.

- Older age (peak adult age 70-80, mostly direct hernias)

- Mechanical load, and

- Perhaps smoking and prostatism.

Both abnormally low and high BMI are reported risk factors but the importance of low BMI is confounded by hernias being more apparent in thin individuals.

Inguinal hernias can be diagnosed by clinical examination alone in most patients.

Ultrasound examination is usually not required but may be considered to examine the contralateral side for a small hernia, although this statement is controversial. Imaging may be indicated to confirm the presence of small groin hernias in obese symptomatic patients.

If a hernia found by imaging is difficult to detect on physical examination, an alternative diagnosis for groin pain should be considered.

The preferred operative method for groin hernias is a laparoscopic totally extraperitoneal (TEP), also known as preperitoneal, repair.

A traditional open inguinal hernia repair may be preferred or required for irreducible, inguinoscrotal, or large diameter defect direct hernias.

The recurrence rate may be higher for large direct hernias repaired laparoscopically as the preperitoneal mesh can just form another layer of the hernia sac.

The following hernias should be repaired even if the hernia is not causing pain or discomfort;

- Enlarging hernias

- Hernias containing bowel, and

- Groin hernias in females (who may have a femoral hernia alone or with an inguinal hernia)

Figure two: Same area as figure one after placement of a soft wider bore pre peritoneal mesh. The mesh is fixed in place with absorbable tacks (purple) and absorbable glue (white)

Approximately 11% of patients who undergo inguinal hernia repair will have a contralateral repair within 10 years.

Since laparoscopic repair is performed through midline incisions it is technically straightforward to repair bilateral hernias and this is indicated if both sides are symptomatic or enlarging.

If only one side is symptomatic then as above an informed discussion is required to make a shared decision as to whether bilateral inguinal hernia repair should be performed.

There has been a dramatic increase in bilateral repairs following the widespread adoption of the laparoscopic approach which seems to indicate that laparoscopic bilateral repair is being performed in many patients who need only unilateral repair, such as those with asymptomatic contralateral hernias without a clinically detectable lump.

Physiotherapy can begin as soon as one week after surgery, if the patient has recovered well. Guidelines for heavy lifting, defined as lifting more than 10kg, have traditionally stated no heavy lifting for 6 weeks based on wound healing data. However, many surgeons now allow a return to regular exercise after one week and lifting more than 10kg after approximately 3 weeks. For recurrent hernias waiting longer for physiotherapy and exercise is recommended.

Nutritional advice should ideally begin weeks or months prior to elective hernia repair for patients who are overweight or obese. The aim is to lose weight both pre- and post-operatively.

FEMORAL HERNIA

- Femoral hernias, shown in Figure 1, are four times more common in women.

- Femoral hernias classically present as swelling inferolateral to the pubic tubercle but the clinical diagnosis can be difficult and ultrasound imaging may be needed to clarify the precise location the hernia, especially in obese individuals.

Figure One: Laparoscopic Pre peritoneal hernia operative view in a female patient. Instrument points to femoral canal after reduction of a femoral hernia.

- Inferior epigastric vessels. Inguinal Hernias medial to this are direct hernia; inguinal hernias lateral to this are indirect hernias.

- Round ligament

The lifetime risk of developing a groin hernia has been estimated at 27% for men and 3% for women, and more than 20 million people undergo groin hernia surgery per year.

- Sex - Inguinal hernias are 9-12 times more common in men.

- Older age (peak adult age 70-80, mostly direct hernias)

- Mechanical load, and

- Perhaps smoking and prostatism.

Both abnormally low and high BMI are reported risk factors but the importance of low BMI is confounded by hernias being more apparent in thin individuals.

UMBILICAL AND EPIGASTRIC HERNIAS

- Umbilical hernia is a primary hernia in the midline with the defect located in the umbilical ring. These are far more common than para-umbilical hernias.

- An ultrasound study suggested that asymptomatic hernias may be present in up to 25% of the population.

- An epigastric hernia is defined as a primary hernia with the centre of the defect located in the midline above the umbilicus and below the xiphoid process.

- Umbilical and epigastric hernias are usually diagnosed by clinical examination alone but ultrasound or CT imaging may be indicated in uncertain cases, such as to identify small epigastric hernias in obese individuals.

- Asymptomatic umbilical or epigastric hernias can be managed by “watchful waiting” without immediate surgery, although adequate data on this subject are lacking and many patients prefer to have an asymptomatic hernia repaired if there is an obvious lump.

- Patients with pain or discomfort should undergo hernia repair and those with strangulation or incarceration should undergo emergency repair.

Meta-analyses of studies including RCTs demonstrate that the recurrence rate for umbilical and epigastric hernia repair is lower if mesh is used, although data for small defects up to 1cm in diameter are lacking.

The European and American guidelines recommend that symptomatic umbilical and epigastric hernias are repaired by an open approach with a preperitoneal flat mesh.

A laparoscopic or robot-assisted approach may be suitable for larger hernias, for example greater than 4cm in diameter, or multiple hernias, but the guidelines note that most laparoscopic repairs performed have involved placing an intraperitoneal mesh, which can lead to adhesions and serious complications.

All types of mesh can cause intestinal adhesions when placed within the abdominal cavity, and simple effective hernia repair methods that don’t involve intraperitoneal mesh (preperitoneal mesh, subrectus mesh repairs) are available.

The prevalence of divarication of the recti is increasing due to rising rates of obesity. This is when the two sides of your rectus adominus muscles separate, which also occurs in pregnancy. The recurrence of Umbilical hernias is more likely in those with divarication, so addressing this at the time of operation may be considered.

Physiotherapy can begin as soon as one week after surgery, if the patient has recovered well. Guidelines for heavy lifting, defined as lifting more than 10kg, have traditionally stated no heavy lifting for 6 weeks based on wound healing data. However, many surgeons now allow a return to regular exercise after one week and lifting more than 10kg after approximately 3 weeks. For recurrent hernias waiting longer for physiotherapy and exercise is recommended.

Nutritional advice should ideally begin weeks or months prior to elective hernia repair for patients who are overweight or obese. The aim is to lose weight both pre- and post-operatively.

This brief review includes the common primary abdominal wall hernias: inguinal and femoral groin hernias, and umbilical and epigastric midline hernias.

It incorporates the guidelines of the British/European/American Hernia Societies and the international HerniaSurge group, with comments from personal experience. Uncommon hernias of the abdominal wall including hernias of the lumbar area in the lower back and the very uncommon hernias of the pelvic floor (obturator, perineal, and sciatic hernias) are not discussed. Secondary hernias including incisional hernias are also not reviewed.